Paper presented at the University of Newcastle Creative Arts Research Symposium, Newcastle, Australia, 9 June, 2016.

I do not condone the use of memoir, surveillance, or any other discourse altering substances.

Writing a memoir involves taking one’s life and smearing it onto the page. When you craft a memoir, it is inevitably a personal experience and cannot be separated from the author except by extreme force of will. What a memoirist does is tell a story, but a story with themselves as subject and author.

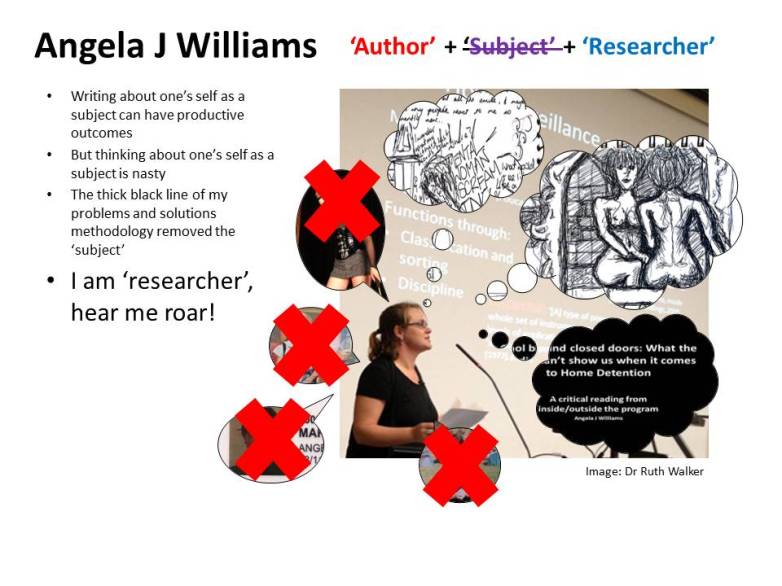

What happens then when you take that memoir, the dual roles of author and subject, and widen it to include researcher?

When the author is subject and the subject is also researcher, how does one draw a line around one’s theoretical investigation?

Carefully, it turns out, and with a thick indelible marker.

My story wasn’t always easy to tell, but doing it within the scaffolding of a PhD allowed me space and support to own my voice and my story.

My research wasn’t easy to undertake, but having a way to cement myself as ‘researcher’ made it easier.

This presentation isn’t about my research, so much as the research process. Living with this cacophony of voices throughout research isn’t easy. I can’t answer the question: ‘Why would anyone write about themselves writing about themselves?’ But it can tell you how I drew that thick, black line.

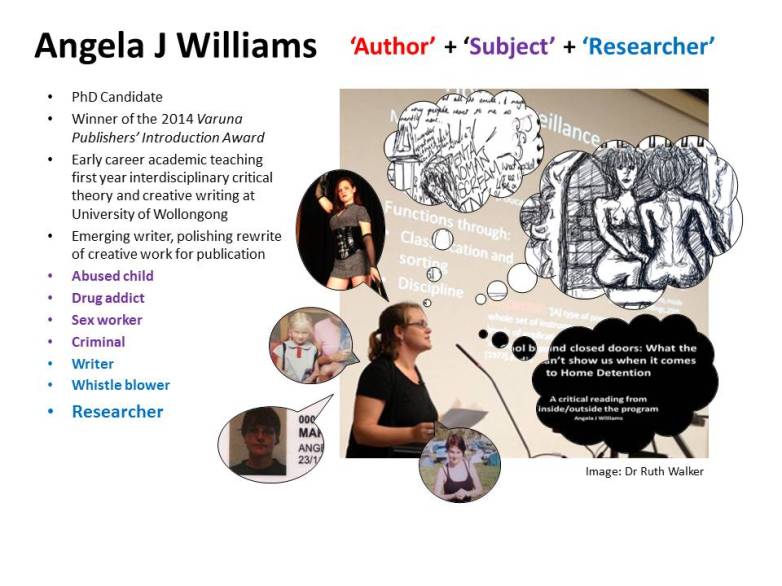

This is me:

I am a writer: autobiographical writer who sees bad stuff happening in my world as research for my writing. But being an author of difficult texts isn’t easy.

Writing trauma, you see, is very different to either living it or talking about it in therapy. When you live through something bad, you have to move past it; have to shift back into the real world.

And when you confront trauma in therapy, you look at it, feel the feelings, have a cry (or scream) and then try to let it go.

When you narrate trauma, as an author, your obligation is to dig as deep into that trauma as you can – to separate it into its tiniest constituents. Examine each shred of the pain to discover which parts have narrative value, plot advancing status.

You take every one of those slivers of trauma and try to find the way, the words, to make your readers feel the same as you did living through the trauma. It’s a not fun process, trust me.

Within the HDR context, you then need to take this self-exposure and share it with at least one other person.

My supervisor, the amazing Dr Shady Cosgrove, saw and heard some parts of me that no-one but my psychiatrist had ever seen. That was hard. For both of us.

Shady reminded me again and again of my thick black line – she talked about my memoir as a novel, myself in the story as a character.

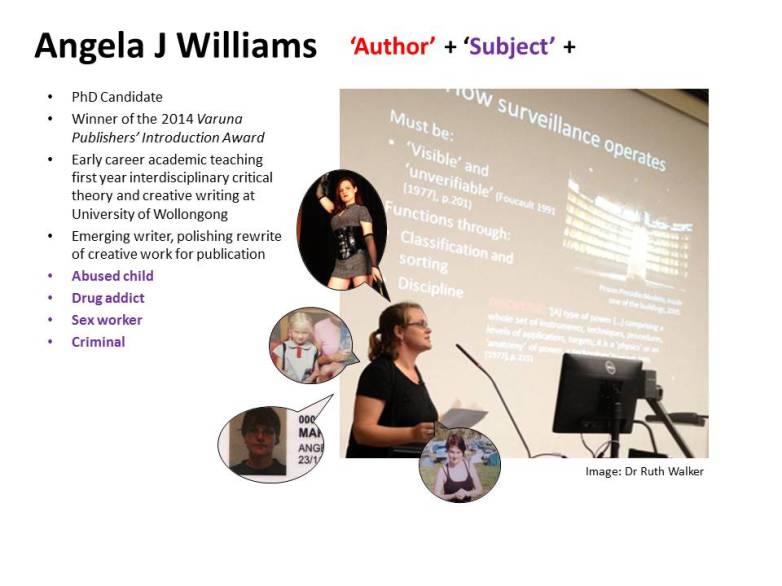

She needed that, and I needed that – for I am much more than what this slide says – I am also Subject:

Writing the story where you are both author and subject is difficult enough, doing it with some not so pretty reflections of myself and some explosive ‘secrets’ to share made it a minefield.

Writing the story where you are both author and subject is difficult enough, doing it with some not so pretty reflections of myself and some explosive ‘secrets’ to share made it a minefield.

We write abstracts for everything – this is how I described my creative work:

I used to be a heroin addict, criminal and all round notnicegirl.

In 1996 I got out of prison for a drug-fuelled crime and promised myself I’d never go back, in 2010 I broke that promise after going to the police as a victim and finding out I hadn’t followed up paperwork from the first time. Snakes and Ladders looks at prison in NSW from both the inside and the outside, showing what it’s like to get caught up in the system again after thirteen years of fighting to escape from cyclic disadvantage. My book breaks out of the walls of the prisons and explores the paths that led to my original crime, including an abusive childhood, struggles with addiction and unhealthy forms of sex work. This compelling story of accountability, tragedy and redemption shows the reality of contemporary women’s prisons, and in some ways can be imagined as a step-by-step instruction guide for how to break out of dangerous cycles of addiction and criminality.

In 2003, after getting clean off drugs, I left that world of crime and addiction behind and went to University. Seven years, two degrees and a lifetime later, I forgot to look right as I crossed a road and was hit by a Postie on her motorbike. When the police came to take my statement they arrested me for an outstanding warrant for time I hadn’t served back in the ’90s. I’d just finished a First Class Honours’ degree at University of Wollongong. Snakes and Ladders tells the story of the six weeks I spent in prison and the following ten months on home detention. In the process of telling this story, I weave vignettes and memories from my early life that reveal the relationships and complications that led to the original crime. But I also explore the people and situations that allowed me to break free from a life that was going nowhere.

Snakes and Ladders blurs the line between creative non-fiction and critical writing, applying an academic understanding of power and discourse to the social structures that most actively embody these concepts. It takes you inside four different prisons, the maximum security Mulawa Women’s Correctional Centre in Sydney, the two medium security prisons at Berrima and Emu Plains, and the collaborative panopticon that Corrective Services and I built in home detention.

‘It’s all a game, you know, a stupid power game which only works cause we play along,’ I write in Chapter 2. This book is about how I worked out the rules of the game and found a way to follow them.

What an interesting story to analyse, right?

The shift from author and subject to RESEARCHER involves not just a reimagining of one’s role, but also necessitates and sweeping out of the more emotional weight, a way to sharpen the ‘researcher’ despite the trauma of the subject.

I am a researcher, thinker, theorist. I like to think about power, discourse, identity. I like to think about memoir.

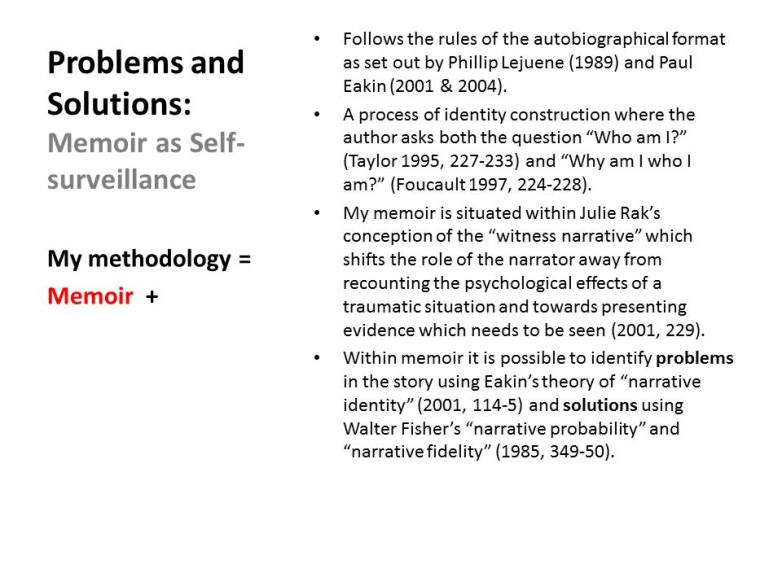

My research reimagines the process of writing a memoir as a form of self-surveillance. It aligns the surveillant functions – classification and risk mitigation – with the memoirist’s shift into narrator mode and self/other protection. Then it looks for the outcomes of surveillance – discipline and resistance – within the formation of a narrative identity and narrative probability. It has a very prescriptive methodology which is turned on three contemporary memoirs. Exciting, right? Then, in exegetical frenzy, it lets loose on my memoir – Snakes and Ladders. My research takes this self-exposure and puts it under the academic lens, trying really hard to follow that thick black line – my methodology.

As artfully illustrated in my slide, the construction of a solid methodology didn’t just separate out myself as author, subject, and researcher, but in many ways allowed me eradicate the question of me as subject entirely.

Taking my cues from Shady, I looked at my subject selves in the memoir as ‘characters’, giving myself the mental space to imagine them as researcher.

I stepped back from the pain and trauma of the story and started to break the parts of it into smaller pieces, find a way to look into this most subjective form with focussed objective lenses.

I made a methodology. A very precise and clear methodology which I could apply to both my own work and other memoirs.

The memoir traditionally covers one period of the author/subject’s life and is usually told for a reason.

The first thing that a memoirist does, before even putting pen to paper, is to realise that there is some situation in their world (often in the past) which they need to share, and in sharing, unpick and explain.

In my research, I have situated this as the shift into narrator mode, the author taking on the restrictions and obligations of a narrator.

While narrators obviously already know the end of the story, they can only tell it from start to end, and this is where the author shifts into a self and other-protective mode.

This drive can be understood both by the author’s drive to write the story and the need to be respectful of both themselves and others who share their story.

As the memoir progresses, the narrator/author is unpeeled in the page and the ‘narrative identity’ starts to emerge.

This narrative identity is the character elements of the subject, those things which allow us to understand them as a rounded and complete character within their own narrative.

The risk mitigation inherent in the formation of the narrative identity and the self/other protectiveness which comes into play here, is imagined in my research as identifying the ‘problems ‘ that exist – what it was to drove then author to write the story.

The shift towards finding solutions occurs as the author takes this narrative identity and shapes it into a form that will be acceptable and understandable to readers.

As the many cases of memoir ‘fraud’ show us, readers respond strongly and negatively to ‘rule breaking’ memoirs, such as Demidenko, etc., and so for the tale to reach a satisfactory ending, the author needs to shape their narrator/subject/author into a ‘normative model’ of narrative identity and bring the story to a satisfying end.

This satisfying end is judged by the rubric of narrative probability.

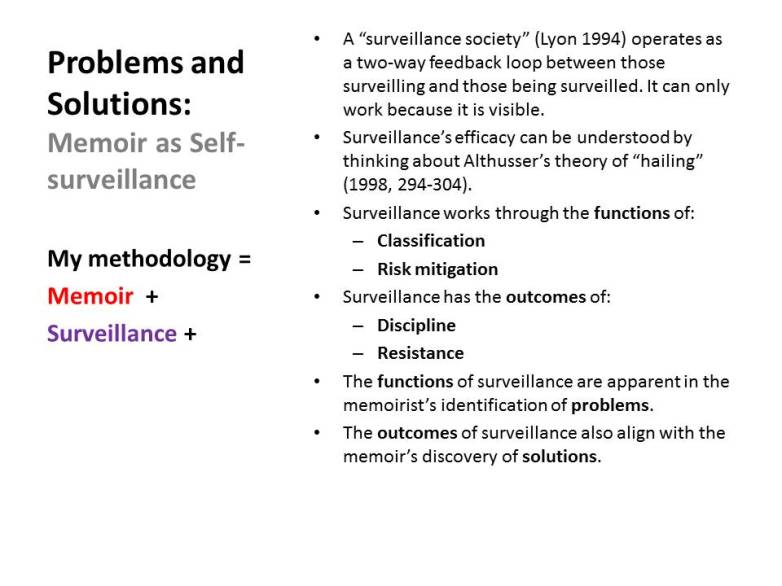

The tools that a memoirist uses to unpick and explain their story in a memoir can, it turns out, be understood more clearly by turning to the analogy of surveillance, in particular self-surveillance.

Surveillance works by a process of visibility (the signs and cameras) and hailing (ALTHUSSER) to remind us that we are being watched, our actions being noted.

Surveillance, in its functions, is primarily a matter of data collection, by governments, big business, service providers and, increasingly, willingly handed over by individuals with our ubiquitous smartphones, fitness apps/devices, and constant need to be logged, tracked and located.

Surveillance came out of the historic drives to separate the sick from the well during ye olde plague eras, and we can still see this classification drive in action today, particularly as we look at racial profiling and questions of ‘national security’.

The need to classify people leads into the second function of surveillance, risk mitigation.

If surveillance can be used to identify the ‘biggest risks’ in society, those uninsurable risks like terrorism, then it can be seen as a form of risk mitigation

These two functions of surveillance then lead towards the first outcome of surveillance, a better-behaved, ‘disciplined’ society where people are more likely to follow the rules because they know they will be found out if they are caught.

But, of course, where you have these naughty people, you also have the nice and so we are caught in a bind when it comes to thinking about surveillance as non-naughty types.

For those not thinking to break the law, then the constant visual reminders of surveillance can act as both an irritant and an inspiration.

In my research, I have identified the second outcome of surveillance as resistance, or the need to fight against a ‘top down’ surveillance, to implement forms of resistance (including artistically) which gives us a space to argue back at the status quo.

This is my methodology – that thick black line. This pattern, which I looked for in all my case studies (including that memoir I wrote), takes away the subject, replacing it with the questions of problems and solutions.

The functions and outcomes of both memoir and surveillance are what allow us to draw an analogous practice between the two.

The surveillant functions – classification and risk mitigation – can be tied to the moments in which the memoirist decides that they need to write the story, the drivee.

They are choosing to classify themselves as both author and subject and then implementing risk mitigation in the way they choose to present themselves in both of these roles.

The exploration of these interweaved strands of function are what are described as ‘problems’ in my research.

Then a shift is made into looking at outcomes.

The outcome of surveillance, discipline and resistance, are exposed in the memoir through the author/subject’s self-discipline and inevitable resistance to the discursive forces which have shaped their role in the narrative and how this story and role aligns with the expectations of narrative probability.

This is seen by my research as the author finding the ‘solutions’ to whatever drove them to write the memoir.

By using the lens of surveillance theory to unpick the obligations of the autobiographical writer, my methodology allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the roles of author/narrator/subject.

It also opens up a path towards a deeper understanding of the development of the narrative identity and its inevitable push towards narrative probability.

This linking of ideas from disparate fields of research allowed me to find new lenses to apply to both my examined case studies and my own memoir.

But did it work? I hear you roar!

This is thick black line’s outcome when answering the question: Can Snakes and Ladders be understood through self-surveillance?

Snakes and Ladders begins with a tangled and divided narrator, unable to bring together the strands of divergent life experiences, and ends with a confident and critical thinker who can see the full spectrum of power as it plays out in the system. In discussing surveillance and discipline in the Methodology, I quoted Foucault saying the person who “assumes responsibility for the constraints of power […] inscribes in himself the power relations in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection” (1977, 202-3), and in constructing this memoir I have indeed become the principle of my own subjection. I have learned how to weight the dice with a careful blend of intellect, inquiry and (often bluffed) confidence and am moving my piece from ladder to ladder with a hand that barely shakes.

The problems that occurred in the memoir, the fracturing of identity and divergence of history and actuality, were uncovered and alleviated by the processes of classification and risk mitigation. By looking closely and honestly at the development of the intersecting identities, I found a way to rearticulate this data in a way that values and legitimises the experiences of both Angelas.

The application of this newly formed understanding of the cohesive personality then acts, as predicted by my thesis, to open up the space for discipline and resistance to be explored and uncovered. Without the understanding and convergence of the different strands of my narrative identities, it would have been impossible for me to tap into and utilise the self-discipline needed to act out the resistance that carries me through to the triumphant final pages of the memoir.

And that’s some pretty sexy summing up, if I do say so myself.

Hang on, which me said that?

Like I said at the start, I cannot tell you why a person would write theoretically about themselves writing autobiographically.

My advice would be: DON’T.

But what I have discovered through my research is that when you are the subject has the potential to be unsettling, the easiest way to manage that is by tying the subject up very tightly in a web of methodology.